Why the “Boss in Disguise” doesn’t solve company problems

The first step to solving a problem is understanding where the problem lies. If sales are down or costs are up, what’s the problem? And how do I fix it?

The natural question—and the need it brings—has opened the market to problem hunters even before solution merchants.

But while machines and processes can be easily assessed by the right technician, what expert do I need if I suspect something is amiss with my staff’s customer management?

The retail sector has grappled with this issue since the early days of department stores in France in the 1830s: managers were so far removed from staff behavior that they couldn’t clearly understand the problem.

And when information and time are scarce, it’s easy to fall prey to irrational decisions.

Imagine you’re the manager of a large restaurant. Which of the following situations do you consider the riskiest for your business?

- Building fire

- Disloyalty or corruption among staff (taking money from the cash register or accepting bribes from suppliers)

- Busy staff (following the customer while continuing with other tasks like cleaning, watering, etc.)

- Theft of inventory or cash overnight.

- No upselling attempts by staff (only what the customer requests is offered)

- Inappropriate staff conduct (ranging from intoxication to making advances on customers)

If the lack of information has had its effect, the alternatives you have selected are those with a strong emotional component (e.g., losing everything in a fire or having an employee betray the owner’s trust). Few, however, will have been concerned about a staff that is busy or unwilling to sell anything other than the product the customer requested.

Emotionality, heuristics and cognitive biases

In other words, the situation has suggested that your decision-making process take the shortcut of availability, that is, in a lack of information – perhaps suddenly catapulted into the role of restaurateur – we consider events with a strong emotional component as more decisive and probable.

(See the studies of Kahneman e Tversky, 1973)

It was enough to mention risks characterized by a high emotional impact to make them more possible and worrying.

A famous example is shark attacks, which are much rarer than you might think.

And this cognitive error (bias) becomes critical even for experienced entrepreneurs who, having to choose which service to use to realign their business results, make use of tools oriented towards investigating sensational or unusual events, but which they consider more critical and probable!

Hence, for example, the rush for extended guarantees – statistically a bad investment – or undercover investigation services (Mystery Shopping) to monitor the sales network or production facilities.

Secrecy factor vs. Certain evidence

This latter model, widely invoked in television formats due to its high appeal –e.g. Spie al Ristorante [T Group, 2012], Boss incognito [Rai, 2014], etc. – bases its approach, and success, on the assumption that a secret and sporadic sampling of staff activity can reveal serious elements crucial to business results, directly attributable to one or more individuals.

It is appropriate to debunk two of the elements of this purchasing argument:

- Secrecy: A key element of the formula is that our agent will be incognito, and this certainly whets our cinephile appetite, satisfied by a purchase that brings us closer to spy films. But is all this secrecy necessary?

The so-called mere-observation effect (mere observation effect), according to which the simple observation of a phenomenon causes its modification, pushes us to confirm this statement. However, this consideration becomes debatable if we are dealing with people’s behaviors. In fact, the behavior of all of us is influenced by our individual past: we have often noticed someone on the side of the road measuring our driving behavior, and the consequences of this situation have taught us to moderate our speed in view of the steering wheel. We reflect on how in the presence of the same steering wheel, however, none of us worry about the fuel level in the tank, adjusting the seat tilt, or fixing our hair.

Therefore, we can say that the observer effect induces a change exclusively in those behaviors that we know are observed and for which we know there will be a consequence. By manipulating these two elements we can make the factor “unknown” no longer so indispensable (especially given the costs we will explore in point 2). - Sporadic sampling, based on the search for sensational events: the second pillar of Mystery Shopping is the hit-and-run approach, not dictated by a methodological choice but by the need for secrecy already discussed; if we want to maintain the unknown, we must necessarily foresee that the same “agent” cannot observe a situation more than once (and much less be able to interact with the entire staff of the point of sale). Therefore, the solution adopted is to recruit a handful of non-professional agents (also to keep costs down) and compromise on the number of data collected: a few surveys focused on finding sensational events.

But haven’t we already experienced this condition, and its effects, by talking about availability of heuristics? How to avoid it?

The only way is to maintain a sense of perspective and base our decisions on certain evidence. And the certainty of evidence comes directly from the number of data collected. To guide us towards this result, let’s try to set aside the secrecy factor for a moment: by doing so, we can build an observation model that, by deploying a small team of meters (one or two people at most), allows us to collect timely and numerous data on staff behavior.

Building a model of behavior observation

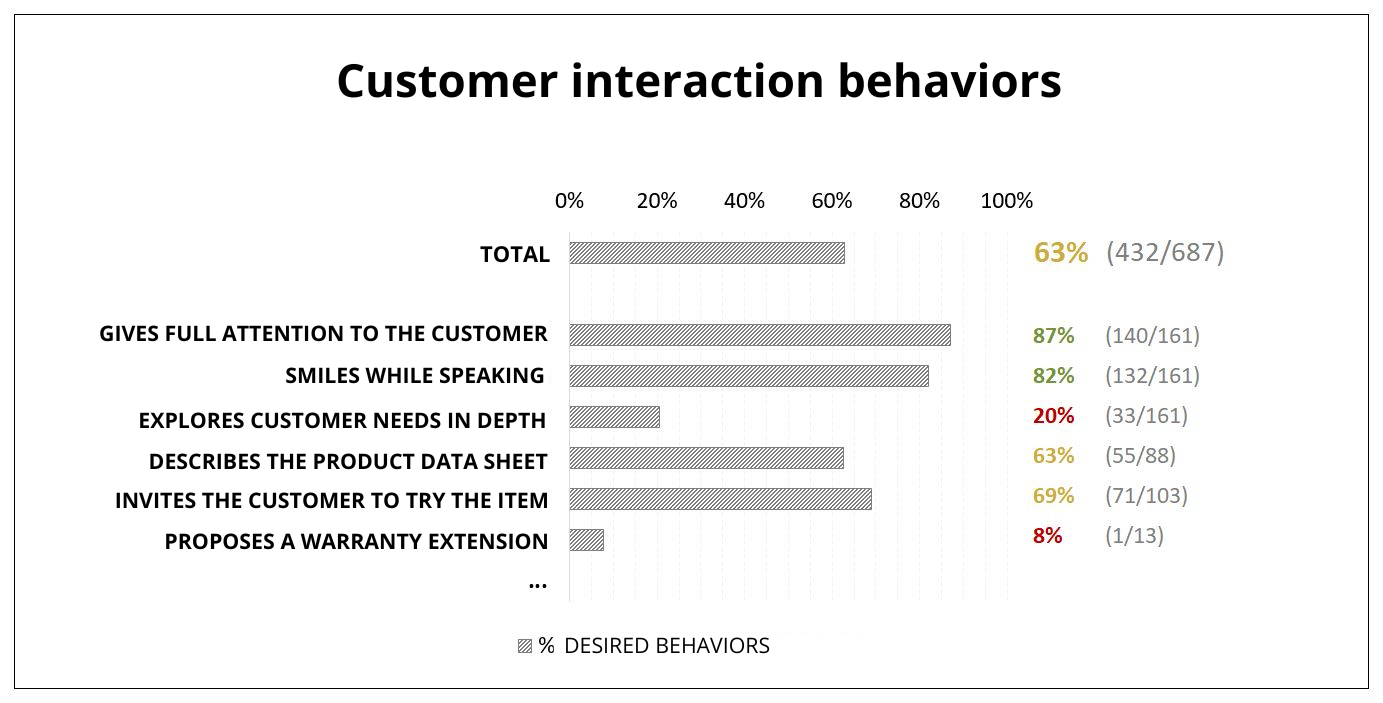

Let’s look at an example of applying the above methodology: the graph on the side shows the frequencies of some behaviors detected in a department of a department store.

The actions on the left are formalized with the help of the area managers and form the measurement instrument used by the collection team.

What emerges is a clear snapshot of the behaviors engaged in, with clear priorities for intervention: I hypothesized a problem related to the attitude of the staff (a particularly rude clerk and a few smiling faces), but looking at the overall picture, I notice much more widespread and crucial behaviors for the business, even if less striking.

Applications like this seek all the information necessary to protect entrepreneurs and managers from the error of perspective: contrary to what is expected, it is not the single event attributable to the individual staff member that disturbs the earnings of a business – or a company – but rather the numerous micro-behaviors widespread, in more or less worrying percentages, within the staff (e.g.: Continue emptying the pallets while answering the customer, interrupt customer support to answer a phone call, open the bottle before reaching the table, print the receipt before asking if an invoice is needed, do not put the tools in the right place after using them, do not attach the diary to the meeting call, etc.).

Furthermore, a method aimed at neutral behavior detection –and no longer oriented towards finding negative things, perhaps bad apples within staff– allows us to notice some rare low-frequency behaviors with a positive impact on business, which would never have been detected and placed at the center of an extension intervention for all staff.

In other words, it is possible to notice whiteflies among our employees, perhaps average if we look at their sales or production performance (neither top performers, nor to be stigmatized for the decline in business), but in possession of one or two effective “tricks of the trade” that will remain their only domain, because they are invisible to the selective attention of the Mystery Agent!

In conclusion, it can be exciting to wear a nose and fake glasses to flush out the beam, but let’s not forget the bed of straw scattered on the floor: it can be useful material for a more durable roof or catalyze the fire that will take away our business!

Articolo a cura di:

Morgan Aleotti

Manager

Management consultant and behavior analyst, he has gained experience in the field of multinational clients interested in achieving productivity, quality, sales and safety results through the analysis and dissemination of goal-oriented behaviors. Worked in particular with companies in the metal, food, chemical, health, steel and service industries. Professor of Behavioral Analysis, he has six publications on the subject.

Read more