Never negotiate for revenge – What the US-CHINA trade war teaches us

What are we talking about?

One of the persuasive communication techniques envisages that in the initial stages of negotiations one can “hurt a little” to move the other from their position, but we must be careful not to fall into sadism, in taking pleasure in the pain we inflict.

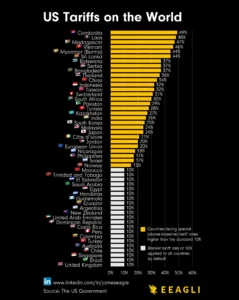

Like many, I am following with passion the evolution of the planetary negotiation on tariffs inaugurated by the President of the United States Donald Trump on April 2, 2025 (“Liberation Day tariffs”). I am far from saying who will prevail because I do not know what degree of self-harm or cruelty humanity is capable of, but I have drawn some personal and professional reflections on negotiation that tell me:

- Why the US approach – at least in the short term – is not working; from which psychological dynamics this approach arises.

- Why can we say that these dynamics are dysfunctional in a negotiation.

- Which path to take when we find ourselves negotiating at work or in business.

I start with an assumption, obvious but important: the negotiation takes place between two or more parties with different perceptions, needs, and motivations who seek to reach an agreement of mutual interest. Let’s focus on the word “mutual“: it implies that the interests of others may be different from ours, or even in contrast, but still legitimate. This premise in turn implies – from a practical point of view, not just an ethical one – that:

My purpose of negotiation cannot be the denial of your interest because this would lead not only to conflict, nor would it satisfy my deepest needs.

Probably, these forms of pleasure or relief have had an evolutionary function: to make us survive in competitive social environments. And perhaps these environments, despite living in the age of abundance, have returned, at least to a psychological level.

But what effect do they have on our coexistence of interests, on our negotiations?

What drives us?

Much of Trump’s electoral success relies on this narrative: “We were once strong and prosperous; then the liberals came, they made us soft, without backbone; the rest of the world took advantage of our weakness and today we have a negative trade balance“. I will not assess the merits of this narrative.

Let’s try to get out of the political aspect and enter the psycological of a negotiation: what effect does it have to enter a negotiation with a feeling of revenge for an injustice suffered, whether that injustice is true?

In fact, when we do, we shift the responsibility for our condition onto someone else: “He or she did that to me and, therefore, I am a victim and I am allowed to take revenge” (spoiler: no, I’m sorry).

Many self-help or business manuals recommend empathizing with the other person, not only when talking to a collaborator, but also when talking to a customer, a supplier, a competitor and – even – with a terrorist kidnapper, as the former international hostage negotiator for the FBI, Chris Voss, explains in his book Don’t split the difference.

There is no shortage of empathy. Emotions determine decisions much more than rational aspects in most cases.

But what I feel like saying, in the light of the experience of the US vs Rest of the World negotiation, is that probably the first person to get in touch with emotions is ourselves. What moves us? Why does it move us? Is our motivation aligned with our values, with our core beliefs?

What if it’s just revenge or retaliation? We should be very aware that after obtaining it – and who knows at what cost – we will still find ourselves there, alone, still with ourselves. And at that point we should find ourselves a new “enemy”, be it Europe, China, liberal…

If we want to benefit from this article, we must remove the thought that makes us feel morally superior to Trump and his staff: “I am not so blinded by hatred, I am not so arrogant, I am not so violent”. Let us question our feelings instead. Let’s think of that client who made us work badly with the other one who paid us poorly, after a thousand reminders and continuous disputes of invoices.

Let us think of that supplier who has made us suffer with his delays and non-compliance. To the collaborator who has missed half of last year’s goals and is now there negotiating new ones.

Here in those moments, on those tables, you may be touched by the desire for revenge. I am not saying that you should not get better conditions in the new negotiation: those are your needs and interests. I’m saying don’t seek revenge for what was. The past is gone, let it go. And so, if anger mounts to you, take a breath and let it go.

If the president and his staff had done this psychological work, they would have avoided Chinese countermeasures that now seem very effective and made the USA take many steps back, until losing much credibility: The questions they could have asked themselves might have been:

- Do we want to increase or reduce the consumption of US citizens?

- Do we want to reduce the rates paid on public debt?

- Do I want to keep the jobs and health of American companies?

- Or do we just want revenge? Just retaliation? Just to return to a past world that we liked?

The short-term effects of the duties were waiting and economists, even of different orientation, were all in agreement with their forecasts.

Negotiation does not like conflict. Nor the guns on the table. Especially if from that table the other side can elegantly get up and walk away

In the book Plaintiff in Chief, New York lawyer James D. Zirin recounted the President of the United States through the 3,500 lawsuits that saw him as plaintiff or defendant. He is evidently accustomed to being in conflict, to having a modus operandi for which it’s “I’ll do things my way and then we’ll see each other in court.”

Negotiating a sale or a purchase is much more like negotiating a military or commercial peace than a dispute in court. In all those cases (sale, peace, etc.), it’s not about ‘settling’ for damage done or suffered; it’s about finding a way to be together, to collaborate, to make a new promise. And if two parties don’t agree, you can’t appeal to anyone to force them to agree… The risk is being left alone holding the short end of the stick.

B2B Sales Excellence

The Lenovys Masterclass dedicated to empowering the skills of sales, marketing, and business development teams, providing tools and methodologies to address complex and multi-level purchasing decision-making processes.

What have I learned by reading current events through my own lenses and expertise?

Never start a negotiation with feelings of revenge, and above all, before beginning a negotiation, empathy towards the other party is fine, but first, let’s get in touch with our own feelings and ask ourselves, “What do I really want?”

What should one do before entering a negotiation

Before starting a negotiation, every salesperson should dedicate time to strategic preparation. As we saw by analyzing the mistakes of the US-China negotiation, freeing oneself from the desire for revenge and creating mutual value are essential conditions for success.

Here are some fundamental actions to take before starting a negotiation:

Let’s remember: excellent negotiators don’t aim to ‘win’ over the other party but to build solid and lasting agreements that create the foundations for profitable future collaborations.

Articolo a cura di:

Alessandro Valdina

Principal

In his university studies there are Communication, Finance and Applied Behavior Analysis. Head of Lenovys' "People & Organization" area, as a management consultant helps organizations achieve safety, quality, production, service and sales goals through measurable improvement in individual and group behaviors. His areas of expertise cover Change Management, Strategy Deployment, Lean Office, Performance Management, Leadership Development and Training Technologies.

Read more